In an opera, the characters stand around for long periods of time singing. If you attempted to judge an opera as if it were any other kind of dramatic performance, you’d complain that no one said very much and they all repeated themselves constantly. The performance would look like nonsense. But an opera isn’t any other kind of dramatic performance. The composer, the librettist, the performers, and the audience all understand this and make the effort to give and take the performance as it’s intended.

How is a computer game intended to be taken? I don’t claim to know the answer to that. I certainly don’t claim to have made a comprehensive survey of the intentions of game designers and players; this isn’t a research paper or a definitive treatise. What I do have is a suggestion that I think could help make good sense of stories in games, both how to tell them and how to take them, based on my own approach after years of playing computer games.

Almost every computer game contains elements of make believe. Even though both involve hand-eye coordination and the index finger, shooting a gun and clicking a mouse are very different actions. But, when I play Counter-Strike and beat an opponent, I’ll say I shot him. This is poetic. Using images, sounds, and a kind of mechanical analogy, the designers of Counter-Strike “map” pointing and clicking with the mouse to aiming and firing with a gun.

The same is true of “walking”, “jumping”, “picking up”, and any other verb in any game. It’s true of all the nouns too. The player is asked by the designer to accept the structures and mechanics he’s built (the gameplay) as metaphors for other things. This is what I meant in Part 1 when I said computer games “simulate events”.

This “simulation”, attaching metaphorical meaning to actions and entities in a game, is the fundamental building block of all characterization and, ultimately, story in computer games.

Obviously these simulations are not complete. Actually they can be extremely tenuous. But this is exactly the same in Opera, or Kabuki theater, or Impressionism. The art is not what it depicts, otherwise it would be reality, but it does depict something.

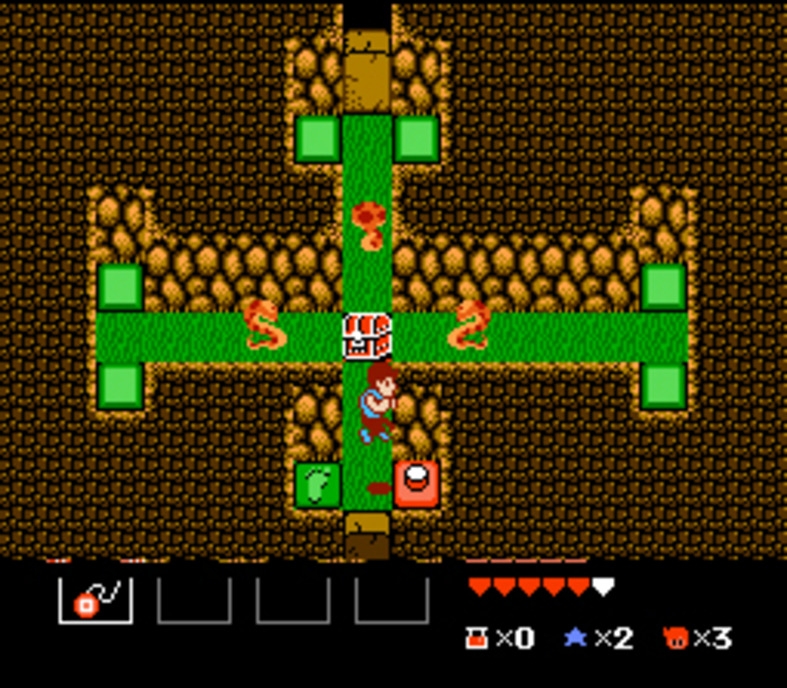

Consider the orange snakes in StarTropics for the NES. They stand still until the player crosses in front of them, at which point they charge in a straight line. Considered purely from a gameplay perspective we can discuss how this behavior affects movement through the environment, the kind of synergies that emerge with other enemies and hazards, etc. But we can also ask whether this enemy behavior is snakey. Does it make sense that this enemy (an element of gameplay) is depicted as a snake?

The answer is yes. Snakes may not stand in one place waiting for you to walk by so they can charge at you. But, the archetypical snake poised to strike does remain still and then lunge suddenly. Given the nature and limitations of StarTropics’ gameplay, given the mechanical space into which the enemy has to fit, a snake is a very good metaphor for this enemy’s behavior.

Given all this, we can think of a game’s story as the sum total of all these simulations interacting and building on each other.

Designers tell these stories by, obviously, building the mechanics and using the metaphors. But they also tell them explicitly by contextualizing gameplay with things like cutscenes. And, the more control the designer wants over the way the story plays out, the more limited and directed the simulations will be. Players also tell stories: by remembering and highlighting things that happen while they play. More robust and unrestricted simulations lead to “emergent” gameplay and lend themselves to this kind of storytelling. (“So the cops were chasing me, and I thought I could make the jump, but I ended up at the bottom of the ravine! The car was totaled!”)

Let’s use these ideas to give Far Cry 2 another look and see how far we get.

Far Cry 2, metaphorically, is a series of more or less isolated vignettes about a mercenary set in the context of an overarching plot. If we imagined the first person perspective of the game to be showing us the literal minute to minute experience of the mercenary, as though he were wearing a Go Pro, the entire thing becomes absurd:

- He never eats, but he casually metabolizes an insane amount of morphine.

- He has malaria, and yet can literally go for days without sleeping.

- He repeats extremely similar missions for various characters over and over.

But taking seriously the nature and limitations of the gameplay, a first person shooter in an open world, we can begin to give the different simulations different weight in the narrative.

- As a gameplay mechanic, the morphine syrettes actually add another interesting wrinkle to an already interesting and multilayered health system. As a metaphor it fits in the setting, and we might say it plays into the “do anything to overcome deadly odds” theme present in the game as you inject addictive narcotics to numb the pain just a little longer. But, you might call it pretty thin, as metaphors go, and pretty jarring to be stabbing yourself in the arm a half dozen times during a shootout.

- Sleeping is a mechanic, but it’s only used as a means of advancing time, which is a perfectly sound metaphor. Requiring the player to sleep would radically alter the pace of the gameplay, and the story just isn’t about taking naps. The malaria thing is trickier, and personally I’m not sure it adds much to Far Cry 2 in either gameplay or story. Having a sudden fit can ramp up the tension in a firefight, but being regularly forced to perform delivery jobs to get more medication doesn’t add much of anything, and in terms of story the player character’s feats of physical prowess seem directly at odds with having a debilitating disease.

- Lastly, the fact that each mission of a given type follows a similar formula adds a kind of rhythm to the game, gives opportunities for variations on a theme, and allows the player to practice. Narratively, we might consider the repetition a metaphor for how it all begins to blur together, one job no different than the next to the jaded soldier of fortune.

We can see that allowing flexibility in the relationship between gameplay mechanics and their metaphorical narrative counterparts doesn’t make a game immune to criticism. What it does do, though, is give a game the benefit of the doubt. It encourages us to go looking for what sense things can make and what kind of stories can be told with the material we have in front of us.

Like I mentioned before, this is how I’ve ended up thinking about mood, setting, and story in games over my 30 years playing them. It isn’t really an observation of how they’re designed, or how other players play them. Yet, I humbly submit these thoughts for your consideration and hope they can be useful in developing story telling conventions unique to our beloved medium.

(The feature image is from this charming old school StarTropics fansite run by Mitch.)